As most of you will know, there are major changes coming up from January 2015 in both the Cambridge: First (FCE ) and the Cambridge: Advanced exams. Both exams move to the four paper format from the five paper format they have had up till now, in line with the changes made in the Cambridge: Proficiency exam last year. Here is a video from Cambridge English TV which explains the changes in the Cambridge: First exam.

Cambridge First

Tips for Speaking Tests (III)

In most Cambridge exams, the candidates work together in pairs in at least some of the tasks. This allows the candidates to use a wider range of language than they could if they were just answering the questions they were asked by the examiner. As they work together, they use language to propose different ideas, express agreement and disagreement and negotiate to a final decision. How successfully they work together is measured in a specific mark, Interactive Communication. Interactive Communication is not only judged when the candidates speak together, it is also observed when the candidates interact with the examiner, but it is most obvious when the candidates work together. In this section, we will look at strategies to improve this mark.

The first thing to say here may seem far to obvious to include – candidates should look at each other during this phase of the test. Too many candidates seem unsure where to look when the collaborative activity begins, and many begin to address their answer to the examiner rather than their partner, requiring further support from the examiner to get them back on track.

The candidate not speaking should also look at his / her partner as they speak, or at the prompt they are talking about, giving non-verbal feedback (nodding, making agreeing noises – ‘mm-hm’, etc.). Some candidates go as far as ‘duetting’, joining in with what the other candidate is saying so that they finish a sentence in unison, or reformulating what their partner has said. All of these strategies are part of ‘active listening’, which forms part of authentic spoken interaction.

An extension of this is to make some reference to what the partner has said at the beginning of the following turn, ‘linking your contributions to those of your partner’. This comes in the marking criteria for FCE and above, but it is useful to train even PET level students to do this in a simple way. Perhaps the easiest way is a simple expression of agreement / disagreement – ‘Yes, I agree with you, but don’t you think…’, or ‘I see your point,, but…’.

Now watch this video of Part 3 of an FCE exam and observe how the candidates work together:

Finally, when interacting either with the examiner or the other candidate, don’t be afraid to ask for clarification if you are unsure what they have said. It is fine to ask ‘Can you repeat that, please’ if you are not sure about an instruction. The examiners are looking for contributions which are relevant, so it is important to know exactly what you are being asked to do. In parts 2 and 3, the key questions are printed at the top of the pages given to the candidates:

Please note that in the exam, the pictures are in colour (images from Cambridge University Press).

Related articles

- Speaking exams: What to do… and what to avoid (davidbradshawenglish.org)

- Tips for Speaking Tests (II) (davidbradshawenglish.org)

- Tips for Speaking Tests (I) (davidbradshawenglish.org)

Speaking exams: What to do… and what to avoid

This post is published in association with TESOL Spain e-Newsletter. For other posts in this series click here.

As the main external exam season starts, I thought this would be a good time to write a post giving tips for how to approach the speaking exams in particular. To kick off, here is a new video from Cambridge English TV with some useful ideas about answering questions in the speaking tests.

Answering the questions

Clearly, you cannot be marked on language which you do not produce, so you should aim to answer questions fully. However, sometimes the question seems to be asking for a simple answer – an apparently closed question with no interrogative pronoun. In this case, the temptation is to give the simple answer, but these questions are provided with a possible back-up question in the examiner’s script – ‘Why?’, so if the candidate does not elaborate sufficiently in their answer, they can be prompted to do so. It causes a better impression if the candidate does not wait to be asked why, but explains and elaborates their answer from the beginning. It shows they are more willing to speak, and gives a more natural feel to the conversation.

There is a great temptation to prepare answers beforehand, particularly for the questions in Part 1 of the test which everyone is asked (‘Where are you from?’ ‘Where do yo live?’ or ‘What do yo like about living there?’, for example). However, it is usually quite obvious to the examiner that an answer is prepared, and it will possibly be cut short. Teachers should be particularly wary of relying on prepared answers for their students. In one examining session last year, I examined eight or ten candidates from the same class, one after another. When asked ‘What do you like about living here in Madrid?’ every one of them spoke of the fantastic public transport system which the city has. Clearly, this quickly became irritating and received no credit.

Language in the speaking exam

In all levels of Cambridge exam, from YLE Starters up to Proficiency, there is, logically, a specific mark for pronunciation. When we talk about this aspect of language, there is a tendency to focus on accent, and specifically whether the candidate is capable of reproducing a particular native speaker accent. However, the examiner is not measuring the non-native candidate against a native-speaker norm. The emphasis is instead on reproducing the individual sounds, intonation and stress patterns of English in a way which does not impede comprehension. While higher levels of exam require the candidate to be ‘intelligible’, lower levels, such as KET or PET allow for a fairly intrusive L1 accent which may make comprehension more difficult at times.

The above video, from the Cambridge English TV channel on You Tube, focuses on word stress, and how a change in stress may mark a change in meaning, and so impede understanding if not reproduced accurately. This word stress can be realised in any accent, native or non-native. Similarly, sentence stress is not dependent on accent. English is traditionally a stress-timed language, as opposed to a syllable-timed language like, for example, Spanish. This means that a successful candidate should be able to place the stress on the correct syllables within an utterance, and at higher levels (CAE or CPE particularly) the candidate should be able to use stress to suplement the meaning of the utterance.

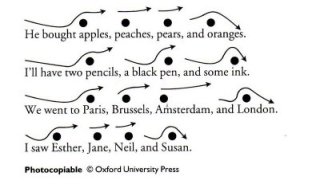

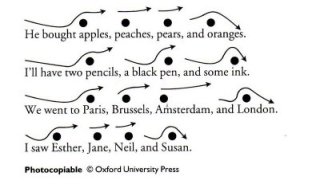

Another important aspect which can be reproduced accurately whatever the accent of the candidate is intonation. A successful candidate should be able to use rising and falling tones within the utterance in order to indicate the internal structure of the utterance, usually rising at the end of each element of a list, for example, or at breaks in an utterance usually represented graphically by a comma, then falling at the end of an utterance, represented graphically by a full stop.This can actually have more effect on understanding at times than accuracy in individual sounds. Several years ago, I examined a PET candidate who reproduced individual sounds accurately, but whose intonation was so wrong that he was almost impossible to understand.

Clearly examiners must also focus on the accurate reproduction of individual sounds. However, different accents imply different versions of individual sounds. Here too, the important thing is to be understood with relative ease, avoiding as far as possible L1 intrusions. It doesn’t matter if the student pronounces ‘Tomato’ as in British English or in American English, but if they say ‘city’ as ‘thity’ (a typical Spanish error, since in Spain, the ‘ci’ and ‘ce’ are pronounced ‘thi’ and ‘the’), that impedes understanding, and so is marked down.

Working together

In most Cambridge exams, the candidates work together in pairs in at least some of the tasks. This allows the candidates to use a wider range of language than they could if they were just answering the questions they were asked by the examiner. As they work together, they use language to propose different ideas, express agreement and disagreement and negotiate to a final decision. How successfully they work together is measured in a specific mark, Interactive Communication. Interactive Communication is not only judged when the candidates speak together, it is also observed when the candidates interact with the examiner, but it is most obvious when the candidates work together. In this section, we will look at strategies to improve this mark.

The first thing to say here may seem far to obvious to include – candidates should look at each other during this phase of the test. Too many candidates seem unsure where to look when the collaborative activity begins, and many begin to address their answer to the examiner rather than their partner, requiring further support from the examiner to get them back on track.

The candidate not speaking should also look at his / her partner as they speak, or at the prompt they are talking about, giving non-verbal feedback (nodding, making agreeing noises – ‘mm-hm’, etc.). Some candidates go as far as ‘duetting’, joining in with what the other candidate is saying so that they finish a sentence in unison, or reformulating what their partner has said. All of these strategies are part of ‘active listening’, which forms part of authentic spoken interaction.

An extension of this is to make some reference to what the partner has said at the beginning of the following turn, ‘linking your contributions to those of your partner’. This comes in the marking criteria for FCE and above, but it is useful to train even PET level students to do this in a simple way. Perhaps the easiest way is a simple expression of agreement / disagreement – ‘Yes, I agree with you, but don’t you think…’, or ‘I see your point,, but…’.

Now watch this video of Part 3 of an FCE exam and observe how the candidates work together:

Finally, when interacting either with the examiner or the other candidate, don’t be afraid to ask for clarification if you are unsure what they have said. It is fine to ask ‘Can you repeat that, please’ if you are not sure about an instruction. The examiners are looking for contributions which are relevant, so it is important to know exactly what you are being asked to do. IN parts 2 and 3, the key questions are printed at the top of the pages given to the candidates:

Please note that in the exam, the pictures are in colour (images from Cambridge University Press).

For ideas for speaking activities, click here.

Related articles:

Tips for Speaking Tests (II)

In the first post in this series, we looked at structuring contributions in the speaking test, giving full, developed answers. In the second post, we are going to look at the language we use in the speaking exam.

In all levels of Cambridge exam, from YLE Starters up to Proficiency, there is, logically, a specific mark for pronunciation. When we talk about this aspect of language, there is a tendency to focus on accent, and specifically whether the candidate is capable of reproducing a particular native speaker accent. However, the examiner is not measuring the non-native candidate against a native-speaker norm. The emphasis is instead on reproducing the individual sounds, intonation and stress patterns of English in a way which does not impede comprehension. While higher levels of exam require the candidate to be ‘intelligible’, lower levels, such as KET or PET allow for a fairly intrusive L1 accent which may make comprehension more difficult at times.

The above video, from the Cambridge English TV channel on You Tube, focuses on word stress, and how a change in stress may mark a change in meaning, and so impede understanding if not reproduced accurately. This word stress can be realised in any accent, native or non-native. Similarly, sentence stress is not dependent on accent. English is traditionally a stress-timed language, as opposed to a syllable-timed language like, for example, Spanish. This means that a successful candidate should be able to place the stress on the correct syllables within an utterance, and at higher levels (CAE or CPE particularly) the candidate should be able to use stress to suplement the meaning of the utterance.

Another important aspect which can be reproduced accurately whatever the accent of the candidate is intonation. A successful candidate should be able to use rising and falling tones within the utterance in order to indicate the internal structure of the utterance, usually rising at the end of each element of a list, for example, or at breaks in an utterance usually represented graphically by a comma, then falling at the end of an utterance, represented graphically by a full stop.This can actually have more effect on understanding at times than accuracy in individual sounds. Several years ago, I examined a PET candidate who reproduced individual sounds acurately, but whose intonation was so wrong that he was almost impossible to understand.

Clearly examiners must also focus on the accurate reproduction of individual sounds. However, different accents imply different versions of individual sounds. Here too, the important thing is to be understood with relative ease, avoiding as far as possible L1 intrusions. It doesn’t matter if the student pronounces ‘Tomato’ as in British English or in American English, but if they say ‘city’ as ‘thity’ (a typical Spanish error, since in Spain, the ‘ci’ and ‘ce’ are pronounced ‘thi’ and ‘the’), that impedes understanding, and so is marked down.

Tips for Speaking Tests (I)

As the main external exam season starts, I thought this would be a good time to write a series of posts giving tips for how to approach the speaking exams in particular. To kick off, here is a new video from Cambridge English TV with some useful ideas about answering questions in the speaking tests.

Clearly, you cannot be marked on language which you do not produce, so you should aim to answer questions fully. However, sometimes the question seems to be asking for a simple answer – an apparently closed question with no interrogative pronoun. In this case, the temptation is to give the simple answer, but these questions are provided with a possible back-up question in the examiner’s script – ‘Why?’, so if the candidate does not elaborate sufficiently in their answer, they can be prompted to do so. It causes a better impression if the candidate does not wait to be asked why, but explains and elaborates their answer from the beginning. It shows they are more willing to speak, and gives a more natural feel to the conversation.

There is a great temptation to prepare answers beforehand, particularly for the questions in Part 1 of the test which everyone is asked (‘Where are you from?’ ‘Where do yo live?’ or ‘What do yo like about living there?’, for example). However, it is usually quite obvious to the examiner that an answer is prepared, and it will possibly be cut short. Teachers should be particularly wary of relying on prepared answers for their students. In one examining session last year, I examined eight or ten candidates from the same class, one after another. When asked ‘What do you like about living here in Madrid?’ every one of them spoke of the fantastic public transport system which the city has. Clearly, this quickly became irritating and received no credit.

Margaret Thatcher ESOL / Critical Thinking Activity: Lesson plan

LEVEL: Upper-Intermediate – Advanced (B2 – C2)

LEVEL: Upper-Intermediate – Advanced (B2 – C2)

TYPES OF ACTIVITY: Speaking; Debate; Compare and Contrast; Essay writing.

OBJECTIVES: The principal objective of this lesson is to help students to develop critical thinking skills while comparing and contrasting two important world leaders. The activity models a structured approach to developing ideas for a writing task or for a class debate

To begin the class, write the following statement on the board:

‘For a leader, it is more important to be strong than to be liked’

Allow the students a couple of minutes’ thinking time, then have them discuss this statement in pairs, focusing on the personal qualities which they consider a leader should have. Once they have done this, join the pairs into groups of four and have them share their ideas. Then each group should report to the class, and an opportunity given to respond and comment. Possible lines of discussion to explore could be the difference between totalitarian and elected leaders, or the difference between being admired and being liked.

Tell the students they are going to read a short biography of a famous leader, and they have to make notes on the main points of the person’s life and decide what qualities they had as a leader. Give half of the class Worksheet A: Margaret Thatcher, and the other half of the class Worksheet B: Mahatma Gandhi. (Here is a link to the worksheets.)

Allow the students to compare their notes with another student working on the same worksheet. Then place the students in pairs with someone who worked on the other worksheet.

First, each student explains the main points of the biography of their leader, and suggests which personal qualities that leader had. Then the students work together to find differences and similarities between the two leaders, recording their answers on a graphic organizer such as a Venn diagram. They should focus on the personal qualities that make each leader different and which personal qualities they have in common, as well as the differences and similarities in their political and social situations.

Once the differences and similarities have been identified, each pair of students must decide which of these can be considered significant in the development of the leader, and draw conclusions about leadership from these significant similarities and differences.

There are different possibilities for a final task to this activity. One possibility would be to ask the students to write an opinion essay with the title ‘What makes a leader great?’ The students would use their notes and ideas from the discussion phase to illustrate their ideas, and to inform their analysis of different leadership styles.

Another possibility is for each pair of students to prepare an oral presentation on the two leaders, focusing on the similarities and differences in their personal qualities. For the presentations, the students should be encouraged to find further information about the personalities and political and social contexts of the two leaders, including recordings of them speaking about their ideas and policies.

Make It Count | Film English

Here’s a lesson plan from Kieran Donaghy that demonstrates a useful way of using video to stimulate discussion in class.

http://film-english.com/2013/04/15/make-it-count/

For more ideas on how to use video in class, click here.

Advanced English Interviews

One of the things which many exam candidates find difficult to do is to acknowledge their partner’s contributions in the collaborative task before launching into their own idea. Here is a resource to help them to improve this area.

ESL Discussions: English Conversation Questions: Speaking Lesson Activities

An incredibly handy resource, whether you are running conversation classes or working on writing with your students.

Speaking Activity: Mission Impossible!

This speaking activity is designed to help your students to revise their written work and improve their critical reading. It is quite a flexible activity, and can be used as a warmer or as a prize at the end of a lesson, or it can form the basis of a lesson in itself.

-

Explain to the students that they are going to create a story as a class, but that the exercise is timed. (I like to play the music from ‘Mission Impossible’ to introduce the lesson – this introduces a sense of urgency.) The time limit depends on the level of the group. I usually use five minutes to begin, then reduce the time as they become more familiar with the game.

-

The timing can be done with a stopwatch on a computer, if possible projected so they can all see the time, or with an egg-timer, preferably one with a loud tick. In any case, they students should have some object which they can pass to indicate whose turn it is, representing the bomb – if they are not passing an egg-timer, a ball will do, but they should pass it carefully, not throw it!

-

The first student is handed the bomb and is told to be very careful! Their task is to dictate the first sentence of a story to the teacher, who will write it on the board. Write what the student says, without judgement, but do not put the full stop until you are satisfied that the sentence is correct. You should not tell the student where the errors are – they must find them and correct them with the help of the rest of the class. Once the sentence is correct, the student can pass the ‘bomb’ to the next student, who has to continue the story with the next sentence.

-

The students each take a turn to add a sentence to the story being created, until the time runs out (the egg-timer rings, or the timer on the board / computer sounds – try to chose a fairly strident sound if possible). The student who is working on his / her sentence when the time finishes is eliminated.

-

If you play several rounds of this game, it is a good idea to make the final round a ‘Zombie’ round, in which only the people eliminated take part. This brngs them back into the lesson, and gives them a second opportunity. I find that they are normally much more careful when revising their work than the first time around.